Introduction to an œuvre: August Walla, by the Collection de l'Art Brut guide Colin Pahlisch

In this column, the Collection de l'Art Brut museum guides regularly take pleasure in sharing the work of their favorite creators with you.

Is art still capable of transforming the world? Now there's a deserving question if ever, given today's all-encompassing appropriations, the pictorial inflation that digital technology now spurs ever onward, digital technology, the way our exhibition spaces have grown in number and manner, as well as how the structural underpinnings of the history of art are being redefined in terms of "modernity" and/or "contemporaneity." With all this in mind, perhaps the key resides less within the realm of official—be it "cultural" as Jean Dubuffet was wont to define it —art. "Cultural" implies art that busies itself overly with seeking to stand out, to make itself known, to figure out the current gallery expectations and museum wishes. That is, too, art that seeks to detect, to intuit even, market fluctuations, all the better to fit in with them. Far more, the answer would and should lie with those for whom creation represents everything, artists for whom the word "art" itself is so precious that "it flees at the very mention of its name" (in the words once more of Dubuffet!).The answer would thus lie with the creators of Art Brut.

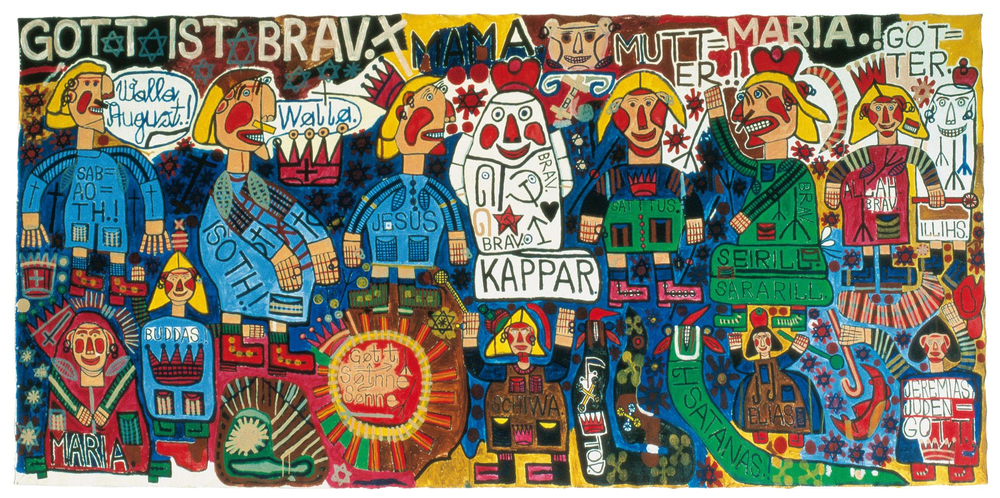

Among such creators, few have delved into art's godlike impact as fervently as did August Walla (1933-2001). Walla was interned at the "Artists' House" of Gugging Hospital (Klosterneuburg, Austria— today named "Gugging Museum"— http://www.gugging.or) from that institution's opening day in 1981. There he undertook the Herculean task of rebuilding the Tower of Babel. In other words, he sought to come up with a universal language based on the known languages of the day, enabling everyone to understand each other. The result was that the languages intertwined, developed and then fell apart bit by bit, to finally clump together into a strange lexicon available to viewers as a large piece on display on the first floor of the Collection de l'Art brut in Lausanne (see illustration).

The psychiatrist Léo Navratil (1921-2006) was Gugging's first director: as such, he commended the use of artistic creation by way of therapy. Visitors might want to imagine August Walla living in a tiny cabin of a family garden along the Danube, with his mother as his only company. He enjoyed drawing, painting, and collecting a diversity of random objects that caught his attention on the street and at public garbage dumps. These he would transform into colorful sculptures that he sometimes photographed.The presence of evil terrified and obsessed Walla: he named it the "evil eye" ("Böser Blick" in his native German). Indeed, his entire oeuvre was an attempt to chase away and ward off evil. Upon being confined to Gugging permanently in 1970 (when Léo Navratil diagnosed him with schizophrenia), he spent his days building a protective oeuvre of an atropaic nature (from the Greek "apotropein"—avert) meant to hold back chaos, to divert misfortune, to forestall conflicts just as one blocks an illness. Hence, the universal language he elaborates is no mere sequence of inert words: it is a performative language. It is meant to affect reality directly, changing it, structuring it, building it up and seeking to better it... Hence, no canvas is big enough, no frame spacious enough. His paintings need to cover the world. Walla thus drew and painted on the Gugging's outside walls, covering as well the walls and floor of his room with sayings and figures. He even went on to colonize the roads next to the hospital with his paint brushes...with an eye to sanctifying his love for his mother. Indeed, we know from Thomas Breymann's writing that Walla wrote these words on the asphalt near the Artists House: "Pfleger sind keine Mutter" (caretakers are no mothers). "Sanctification" is the exact word. The spiritual is central to August Walla's oeuvre: whether seeing himself as a defender of divine justice or else as a universal peacemaker, in any case his is a transcendent act. (His "Götter" painting incorporates all of mankind's religions).His unique and federating language represents an attempt to establish harmony: as such, it constitutesa sacred undertaking, as well as a plea, a struggle on behalf of mutual understanding among all peoples.Thus, the two self-proclaimed virtues attributed to August Walla's oeuvre are its visionary and healing virtues. In the manner of a shaman, the graphic and pictorial gestures constituting his oeuvre are said to stem from the original equilibrium lost to Man. Walla's mission then was to rebuild what was lost, to reincorporate it into reality for the sake of saving and healing it.

Is this magic or a fraud?Is it pathological or prophetic, a miracle or a hoax? The question lies elsewhere. Whether his oeuvre can or not save mankind, Walla's creations can be credited with reminding us of a truth that painters, sculptors and official collectors, ever grasping for recognition, too often tend to forget. Art characterized by detachment simply does not exist.